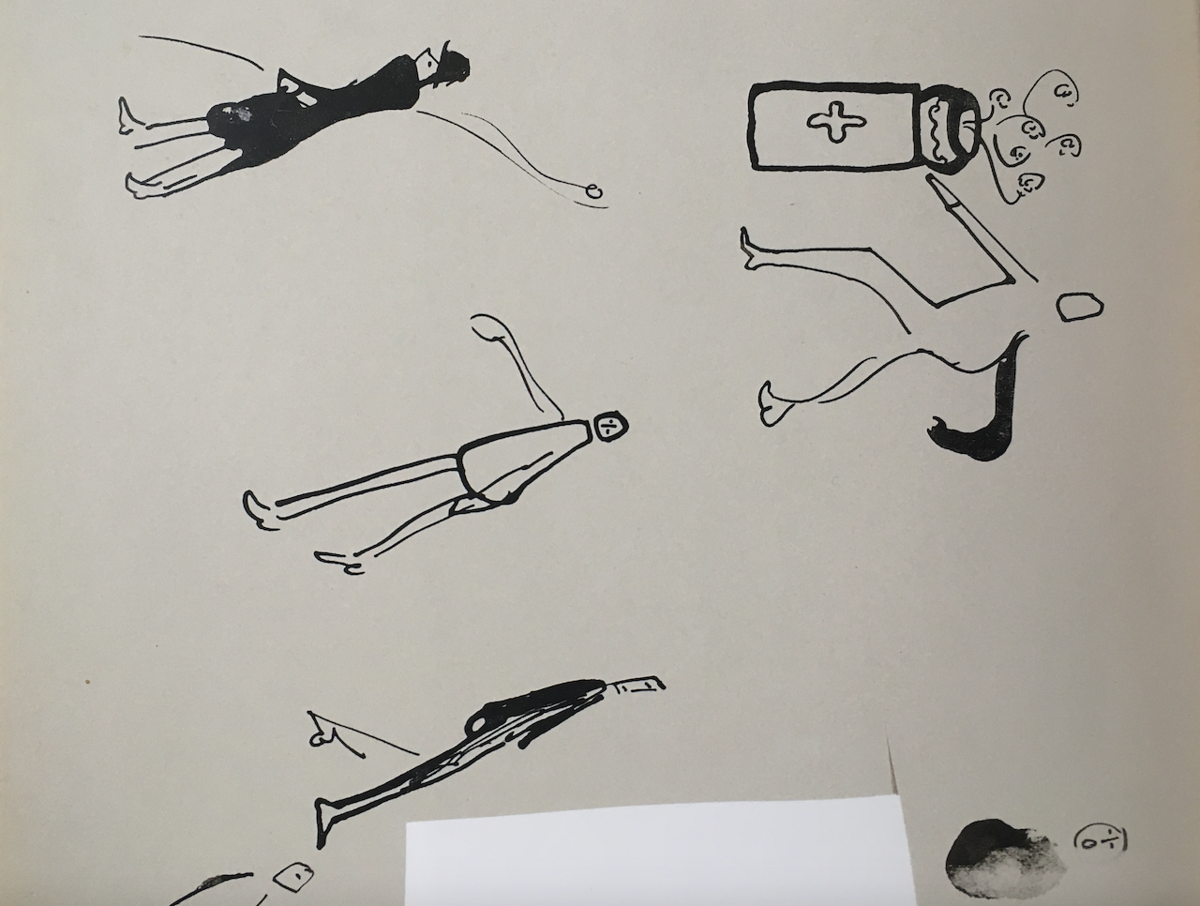

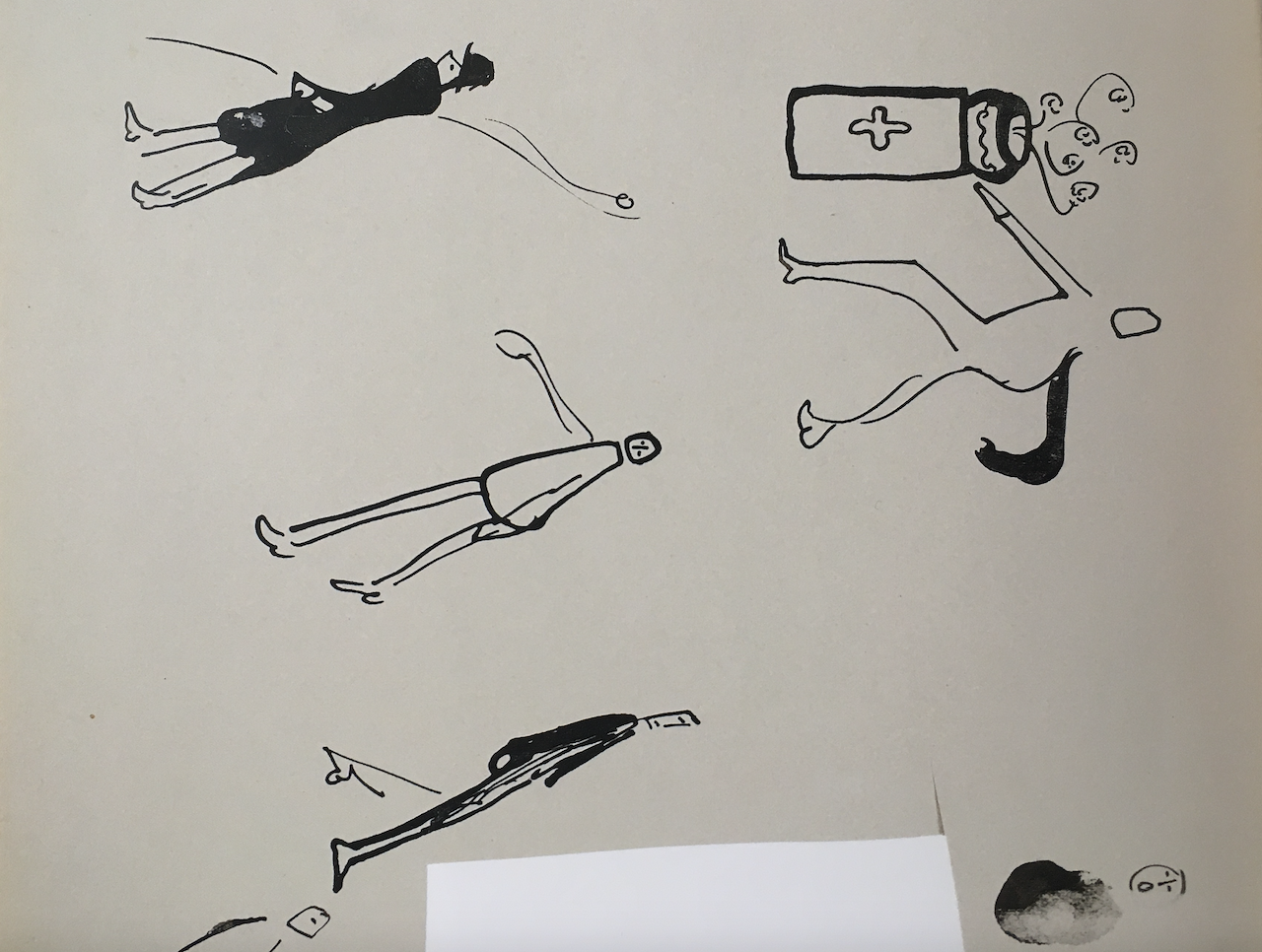

Detail of drawing by Franz Kafka. Photo: Ardon Bar Hama.

This is an excerpt from Ben Ware, On Extinction: Beginning Again at the End, out in March from Verso.

In September 1913, from a sanatorium in the town of Riva, on the northern shores of Lake Garda, Kafka wrote the following lines to his friend Felix Weltsch: “No, Felix, things will not get better for me. Sometimes I think I am no longer in the world but am drifting around in some limbo.”1 A few years later, in 1917, Kafka returned to Riva and to the uncomfortable thought expressed to Weltsch, but this time in fiction: in his texts concerning the Hunter Gracchus.

The Hunter Gracchus material comprises two related works of the same name: a short story and a “fragment,” both unpublished during Kafka’s own lifetime.2 The story begins with a cinematic tableaux, which introduces us to the quiet melancholy stillness of an Italian piazza:

Two boys were sitting on the harbor wall playing with dice. A man was reading a newspaper on the steps of the monument, resting in the shadow of a hero who was flourishing his sword on high. A girl was filling her bucket at the fountain. A fruitseller was lying beside his wares, gazing at the lake. Through the vacant window and door openings of a cafe one could see two men quiet at the back drinking their wine. The proprietor was sitting at a table in front and dozing.3

None of these figures appear to notice the arrival into the harbor of a sailing boat, from which emerges the body of a man carried on a bier. The man is transported to “a yellowish two-storey house” near the water, where his coming is marked by a flock of doves assembling at the front door. Once there, he is laid out on the first floor and the cloth covering him is thrown back, revealing “a man with wildly matted hair, who looked somewhat like a hunter. He lay without motion and, it seemed, without breathing, his eyes closed; yet only his trappings indicated that this man was probably dead.”4

Appearances do, indeed, prove to be deceptive. For the mayor of Riva, Salvatore, then steps forward and lays his hands on the brow of the recumbent figure, at which point the latter awakens. After some formalities—in which the man’s identity is duly confirmed as “the Hunter Gracchus”—the pair engage in dialogue: “‘Are you dead?’ [asks the mayor]. ‘Yes,’ said the Hunter. ‘As you see’ … ‘But you are alive too’ said the [mayor]. ‘In a certain sense,’ said the Hunter, ‘in a certain sense I am alive too.’” The Hunter Gracchus is therefore living, but only in a certain sense. As he tells the mayor, he fell to his death “a great many years ago” while hunting a chamois in the Black Forest, and yet he remains alive because his “death ship lost its way.” What caused this to happen is not exactly clear. Maybe “a wrong turn of the wheel” or “a moment’s absence of mind” on the part of the ship’s captain, Gracchus suggests. What is clear, however, is that the Hunter has missed his encounter with death and is thus condemned to “remain on earth,” his vessel blown about by the winds on the “earthly waters.”5

Whereas Kafka’s canonical mid-period works (“The Judgement,” The Metamorphosis, “In the Penal Colony,” and The Trial) all culminate in death scenes, the protagonists of the 1917 short stories (“The Country Doctor,” “The Cares of a Family Man,” “The Bucket Rider,” and “The Hunter Gracchus”) are all marked by the fact that they are unable to die.6 In one of his reflections on the Gracchus tale, Adorno suggests that the Hunter is the bourgeois class that has itself “failed to die.”7 While such a reading makes good on Adorno’s claim that politics lodges itself most deeply in modernist works that present themselves as politically dead, here we might push this point even further, shifting it more concretely in the direction of our current conjuncture.8

The Hunter Gracchus is undead: whilst he is “always in motion,” he nevertheless goes on without a foreseeable end and therefore without a purpose.9 He exists in a twilight world, an uncanny third space between the living and the dead. His survival figures as a kind of existential insomnia from which there is no clear line of escape. Putting the point in more explicitly psychoanalytic terms, we might say that Gracchus occupies a zone between two deaths. Lacan famously discusses this extraterritorial domain in relation to Sophocles’s heroine Antigone.10 On account of the latter’s refusal to compromise on her desire to secure a burial for her brother Polynices—against the orders of Creon (her uncle and King of Thebes)—Antigone is symbolically murdered: buried alive in a tomb, cancelled from the world of the living (although she is not yet physically dead). As she laments:

No wedding-day; no marriage music;

Death will be all my bridal dower.

[…]

No friend to weep at my banishment

To a rock-hewn chamber of endless durance

In a strange cold tomb alone to linger

Lost between life and death forever.11

While Gracchus and Antigone both find themselves forced to live their own deaths, their cases are nevertheless reversed in two distinct ways. First, Gracchus’s status as undead derives from the fact that his symbolic death has been interrupted (his “death ship,” he claims, has veered off course). Antigone, by contrast, is symbolically dead (persona non grata, excluded from the social body) but biologically she lives on (at least until her eventual suicide). Second, Antigone knows full well that she has transgressed the law, and indeed she provides a wonderfully eccentric explanation for her act of defiance: “I could have had another husband, and by him other sons, if one were lost; but, father and mother lost, where would I get another brother?”12 Gracchus, on the other hand, cannot understand or explain his situation beyond endlessly repeating the tale of his accident. When asked by the mayor if he might bear some responsibility for his “terrible fate,” he abruptly replies: “None.”13 The mayor then asks, “but then whose is the guilt?,” to which Gracchus responds: “the boatman’s.” But the boatman cannot be responsible for Gracchus’s predicament if the latter’s ship “has no rudder” and is driven only “by the wind that blows in the undermost regions of death.”14

Cracks in the Hunter’s narrative begin to appear. Who—or what—has really prevented the man from the Black Forest from dying, condemning him to a state of eternal wandering? Gracchus’s final speeches to the mayor provide an important clue:

I am forever on the great stair that leads up to [the next world]. On that infinitely wide and spacious stair I clamber about, sometimes up, sometimes down, sometimes on the right, sometimes on the left, always in motion … But when I make a supreme flight and see the gate actually shining before me I awaken presently on my old ship, still stranded forlornly in some earthly sea or other. The fundamental error of my onetime death grins at me as I lie in my cabin …

Nobody will read what I say here, no one will come to help me; even if all the people were commanded to help me, every door and window would remain shut, everybody would take to bed and draw the bedclothes over his head, the whole earth would become an inn for the night … The thought of helping me is an illness that has to be cured by taking to one’s bed.15

Here, then, we might suggest the following reading: If anyone is responsible for Gracchus’s undeadness it is Gracchus himself. He cannot die because he cannot stop lamenting the fact that he is not dead; he cannot stop turning over—and therefore secretly enjoying—the agonies of his own situation. Fantasies of a self beyond help, endlessly recycled tales of wounded innocence, nostalgic reflections about the good old days when his “labours were blessed”: Gracchus is locked into a discourse of despair and it is precisely this that holds him in limbo. To cite a wonderfully pertinent passage from Kierkegaard’s The Sickness unto Death: “The torment of despair is precisely [the] inability to die … To be sick unto death is to be unable to die, yet not as if there were hope of life; no, the hopelessness is that there is not even the ultimate hope [of] death … Despair is the hopelessness of not even being able to die.”16

For Gracchus, then, there is no death and no life, no departure and arrival, no damnation and no salvation—just a restless wandering around in perpetual torment, compulsively repeating his “old, old story.”17

If despair proves to be key to Gracchus’s predicament, then we also need to grasp despair as something dialectical. As Kierkegaard’s pseudonym Anti-Climacus paradoxically suggests: despair is the most dangerous illness which, at the same time, is the worst misfortune never to have suffered from.18 It is both a curse and a blessing—something to be both regretted and affirmed. Consumed by despair, the subject is not itself, but it becomes itself only by having despaired. The way out of despair, then, is through despair itself: “One must despair with a vengeance, despair to the full, so that the life of the spirit can break through from the ground up.”19 Or as Anti-Climacus puts it elsewhere: to arrive at the truth “one must go through every negativity, for the old legend about breaking a certain magic spell is true: the piece has to be played through backwards or the spell is not broken.”20

Looked at from this perspective, the problem with Gracchus’s despair is, quite simply, that it isn’t radical enough—it doesn’t go right to the very end. Or, to put things in more Lacanian terms: Gracchus gives way on his despair. He still longs to “solve” the riddle of his accident; still wants reassurance from the big Other (Mayor Salvatore) that he hasn’t “sinned”; still secretly hopes that the townspeople might eventually rise from their beds and “come to help” him. Except, of course, that all this is just part of his problem. Only resolute negativity—the courage of militant resignation—would allow the Hunter to finally bring his living death to a definitive end.

We can cast this dialectics of despair in more directly political terms. Despair, we might say, is born out of social disrepair, a disintegration of the social bond. If despair is, in one respect, capitalism’s “final ideology,” then it also implies a total divestment of hope from the system that produces it, a rejection of its endless false promises.21 Conceived of dialectically, despair is not the belief that nothing would be better than something; rather, it is a revolt against what merely is—a desire (however concealed or inchoate) that things should be otherwise. In this respect, despair is a negative passion that can also function (in Fredric Jameson’s phrase) as a “class passion,” a revolutionary affect.22 By abstaining from the “positive,” by opening ourselves up to the force of despair, we arrive (potentially at least) at a properly political truth: the problems we confront cannot be resolved within the existing framework, and so it is the framework itself that must be transformed.

We thus despair so that despair won’t be given the final word, so that at some future point we can—collectively—have done with the despairing mode of life altogether. Indeed, despair already points in the direction of its own overcoming. As Adorno observes in Negative Dialectics: “Grayness could not fill us with despair, if our minds didn’t harbour the concept of different colours, scattered traces of which are not absent from the negative whole. The traces always come from the past, and our hopes come from their counterpart, from that which was or is doomed.”23

Thus understood, Kafka’s famous remark that “there is hope, an infinite amount of hope, just not for us” can be given a new twist. We might instead say that hope can only be arrived at by way of despair; but even then it is only ever hope for the hopeless, the dead—those whose past dreams of liberation it remains our political duty to summon back to life in the here and now.

Kafka, Letters to Friends, Family, and Editors (John Calder, 1978), 102.

Exactly how many Hunter Gracchus texts there are remains a matter of some debate. In his diary entry for April 6, 1917, Kafka sketches a fragment in which a narrator describes a “tiny harbor” where a “strange boat lay at anchor.” The boat is identified as belonging “to the Hunter Gracchus.” Kafka, Diaries: 1910–1923, ed. Max Brod (Schocken Books, 1949), 373. This is clearly the germ of the two famous Hunter Gracchus texts. But there is also the germ of this germ in his diary entry for October 21, 1913, written shortly after Kafka returned from his stay at Riva (p. 234). I draw here on the two key texts contained in The Complete Stories.

Kafka, “The Hunter Gracchus,” in The Complete Stories (Schocken Books, 1971), 226.

“Hunter Gracchus,” 227.

“Hunter Gracchus,” 228.

John Zilcosky, Kafka’s Travels: Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing (Palgrave, 2003), 185.

Adorno, “Notes on Kafka,” in Prisms, trans. Samuel and Shierry Weber (MIT Press, 1996), 260. Adorno also goes on to say that “Gracchus is the consummate refutation of the possibility banished from the world: to die after a long and full life” (p. 260).

Adorno, “Commitment,” in Notes to Literature: Volume Two, trans. Shierry Weber Nicholsen (Columbia University Press, 1992), 94.

“Hunter Gracchus,” 229.

Lacan, Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book VII: The Ethics of Psychoanalysis, ed. Jacques Alain-Miller, trans. Dennis Porter (Norton, 1997), 299–348.

Sophocles, Antigone, in The Theban Plays, trans. E. F. Watling (Penguin, 1947), 148–49.

Antigone, 150.

“Hunter Gracchus,” 229.

“Hunter Gracchus,” 230.

“Hunter Gracchus,” 228–30.

The Sickness unto Death, trans. Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong (Princeton University Press, 1980), 18.

“Hunter Gracchus,” 233.

Sickness unto Death, 26.

Here I cite to the Alastair Hannay translation of Sickness unto Death (Penguin, 2004), 91.

Sickness unto Death, 44 (Hong translation).

Adorno, Negative Dialectics, trans. E. B. Ashton (Routledge, 2004), 373.

Jameson, “Marx’s Purloined Letter,” in Valences of the Dialectic (Verso, 2009), 143.

Negative Dialectics, 377–78.